Why Design Students Should Watch Films

And no, not movies

Last year, I had an opportunity to teach design history to first year students (or freshmen as they might say in the U.S.). It was a dream come true for me.

After reviewing how the course was taught over the past few years, I fully revamped the curriculum to ensure that students were exposed to a much broader set of visual media and historical and aesthetic concepts. My objective was to help students discover visual and written systems of meaning that would connect with them personally and be valuable in their beginning design practice. I also developed lesson plans that gave students full license to think deeply and critically about design and visual production when examining diverse designers, works or genres.

To create that historical breadth and analytical depth, I added film to the mix. When I was a college student first studying art and critical theory, it was my introductory film classes, and the professors that taught them, that were the most transformative. We learned the early language of film, the poetics of 1920s cinematography, the logic of mise en scene, and why eyeballs being sliced across a sky both were and were not real. (The poet and semiotician Keith Waldrop happened to love early Dadaism and, it turned out, so did I and everyone in the class.) While I’m no Waldrop, I wanted a similar experience for my students.

So, film. Why use the word “film” instead of “movies” or, Lord have mercy, “cinema”? The use of the word “film”, when it comes to everyday parlance, has gone out of fashion, in part because it reflects a very rarefied kind of work. “Movies” means frolicking fun and fantasy. “Film” on the other hand suggests meaningful and momentous motion pictures.

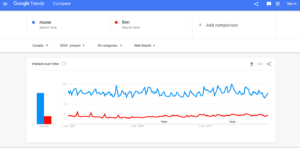

If you have a look at Google Trends’ chart of “film” vs. “cinema” between January 2004 and today, you’ll see kind of what I mean. Most people on Google, including me, are searching for movies (a genre which of course is being eclipsed by gaming, social media, and other media consumption). Film is another thing altogether — more closely aligned with art, technology, and commentary, film has a consistent and transgressive meaning. In this way “film” is ahistorical — so much the better to use in a course on design history.

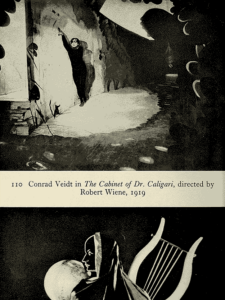

What films did we look at in design history class? After reviewing a few dozen options, I narrowed it down to three: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari(1928), Metropolis (1930) and Man with a Movie Camera (1924). All three of these films share certain characteristics: silent with soundtracks and European in approach, they are black and white and fiercely independent of other films at the time. All three films broke the nominal rules of cinema as well. Caligari used expressionist, painted sets and outrageous dress and props to heighten feelings of claustrophobia and social angst. Metropoliswas the most expensive film of its day, with massive sets and special effects that would still be difficult to pull off today. Man with a Movie Camera has few verbal cues, showing the possibility of a contented, working society through vignettes of everyday life and zero conversation.

I introduced each film and provided social and political context prior to showing them. After watching 20-minute clips at 8 o’clock (yes, 8 AM) in the morning, I expected at least a third of the students to be asleep. But when I turned the lights back on, none were sleeping — or maybe one was. Instead of snoring, there was a collective groan. The group wanted to watch the rest. Our conversations and group discussions after the film clips were wide-ranging and sometimes difficult, taking on topics of surveillance and technology, economic class, and the role of language in storytelling.

Design students (and probably students generally) are simply hungry for historical film. As contemporary producers and communicators, film of the past speaks to them in beautiful, powerful, motivating ways. In part, I think it’s because film, now over a century old, offers students a bit of permanence in an age of endless digital detritus. Sure, posters and paintings have similar qualities — but film — because it is the antecedent to movies and video — feels and therefore is more relevant, more relatable and, in so many ways, much more real.